WWII, Korea Battle Veteran Enlisted at 15

The Forde Files No. 124

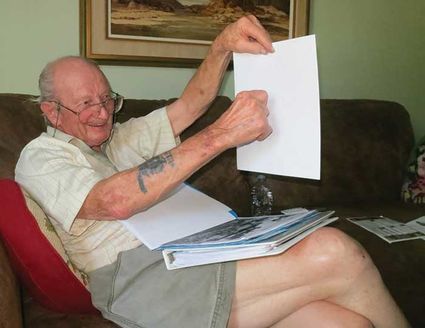

The sound of a bullet –Battle-scarred U.S. Marine veteran George Williamson snaps his finger on a sheet of paper to illustrate the sound of an enemy bullet as it whizzes past a soldier's head. "The bullet is causing a break in the air," he said. "When there are close sounds like that, then you know you're being shot at personally."

George M. Williamson, 87, of Bear Valley Springs, saw fierce action in WWII and Korea; the Marines called him again during Vietnam.

George Williamson was 12 years old in 1941 when the expanding Japanese empire attacked Pearl Harbor and drew the United States into the global conflict that had been going on since 1939. A native of Cincinnati, Williamson had lost his parents in a car accident. His mother's sister adopted him, and he went to live on the forested, sparsely populated Mercer Island, Wash., where he shot rabbits and squirrels for food, swam in Lake Washington every day and took the Dawn Ferry to attend Franklin High School in Seattle.

With an $800 payment from his late parents' insurance, he was able to leave high school and pay his tuition to attend the Puget Sound Naval Academy at Winslow, Bainbridge Island. The Navysanctioned school prepared boys 12 to 18 for entry into the Naval or Coast Guard academies.

During his three years as a high school and academy student, the global conflict had engulfed all of Europe, the Pacific, South Pacific and Southeast Asia, and had become World War II. The Life Magazine graphic pictorial history of World War II later would call 1942 "The Desperate Year." The Philippines had fallen. The U.S. Pacific fleet was virtually wiped out. The Japanese were shooting prisoners of war. Japan had taken several remote U.S. Aleutian Islands and was sending submarines and incendiary balloons along the U.S. Pacific Coast. Nineteen-forty-three was a bloody trail of island and sea battles across the Pacific.

Japan, Williamson said, "Saw us as a huge cherry tree that had everything. We had all the natural resources their country could use – coal, iron. They had many people and no natural resources."

Japan had developed a far-reaching plan for domination, he said, and if we were to re -capture lost territor y, "we needed to get on our horse and take it back."

He signed up as a reservist at the Sand Point Naval Station in Seattle, where he flew over Puget Sound every Sunday in a 60-foot, helium-filled blimp to spot submarines. The blimp cabin held two observers plus the pilot and co-pilot.

The diesel-powered subs would surface during the day to recharge their batteries, Williamson said. They would shell targets early in the morning and at sunset and then dive.

"We never found one [submarine]," he said, although sometimes the shells from the 5-inch diameter submarine deck guns ended up in someone's back yard.

Williamson began working on the Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber flight line at Sand Point.

"I was training to go to the South Pacific, where I would wind up as a gunner or on the deck of an aircraft carrier as part of the flight crew."

For teenager Williamson, it was too far from the real action.

"I wanted to be taking back that land we lost, so I joined the Marine Corps."

It was 1944. He was 15 years old and lied about his age to enlist at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego. He told them he was 18.

"The rest became a blur," he said.

After boot camp and further training at Camp Pendleton, he was attached to the First Marine Division and shipped directly to Guam, which the Japanese had just surrendered. The Marines' job was to find the Japanese soldiers and snipers still hiding around the island in caves and in the heavy jungle.

"The snipers would shoot selectively – usually at an officer. Then they would not shoot again, and would hide."

The Japanese were organized, welltrained, tough and good shots, Williamson said. They had support services and command coordination. Even at the end of the war in the Pacific, the organization was still there.

"They put up a whale of a battle."

When given the option to surrender or get shot, he said, most often they would choose to be shot.

"They would fight until the death," Williamson said. "You could count on one hand those willing to surrender – that was during the first part [of the hostilities]. After the major battles at Iwo Jima and Okinawa they saw the light."

His time on Guam was "training for bigger things."

Those "bigger things" were the Marine assaults on Iwo Jima (beginning Feb. 19, 1945) and Okinawa (beginning April 1, 1945). (See sidebar)

At this point, he said, the U.S. was running out of men.

"Not many red-blooded American boys could do this. You had to be young, strong...and trainable.

"They had to be good shots and able to withstand the routine of war. It goes on 24 hours a day without letup."

Williamson was promoted from Sergeant to lieutenant ("When they ran out of lieutenants"). After the hostilities, the Corps made him a sergeant again to save on the government paycheck.

He recalls the men he fought beside and the ones he lost. He had a platoon of 25 men that was divided into three squads.

"You get to know these guys pretty well. Your commanding officers you meet once or twice. You get to know each other [in the platoon] pretty quick. There's not a lot of bullshit. If you are in a jam or wounded, you are not going to be forgotten. You will be rescued, treated well, fed. You will recover from your wounds. You will not be abandoned to the enemy. Wherever you go, that's the rule of the game. If you are about to lose a fight your friends come to your aid without hesitation, and they would go down with you if necessary with a hell of a fight. They are willing to die. It's a creed – an agreement among all Marines. It happens any time – at an amphibious landing or commitment to combat. It happened regularly."

A wounded Marine, if he were not hit seriously in the body, would argue at the Command Post to be sent back to the fight, saying "Wipe me up and let me go back to my outfit."

As the Americans and Allies dismantled the Japanese empire island by island, the last few battles, Iwo Jima and Okinawa, were ferocious and bloody final stands for the doomed Japanese.

"We paid a heavy price for Iwo Jima," Williamson said.

Among those killed was a friend of Williamson who was a priest embedded with the troops.

Iwo Jima, an ugly volcanic rock, was a source of sulphur for the Japanese. It smelled terrible, Williamson recalls, and the black volcanic dirt made everything grimy. The famous Mt. Suribachi, which the Marines fought so hard to win, is just 554 feet high. It was another company that planted the flag in the famous photo by Associated Press Photographer Joe Rosenthal, Williamson said.

Iwo Jima was 36 days of straight fighting, he said. Okinawa was longer, 44 days. The relentless fighting was 24 hours a day. Everyone was dog-tired, with almost no sleep.

"It is a dirty, filthy, hot job," he said.

Ultimately the job was done. The Navy established outside showers and pumped in fresh water. They issued the Marines new clothes and got rid of the old ones.

The Marines had two types of food boxes. They received K-Rations in their 70-to 80-pound packs before landing; these included cookies, crackers, jam, a cocoa wafer, a package of coffee with one or two creams and three cigarettes.

"We taught all of our personnel how to smoke and drink and a lot of other stuff."

The C-Rations included all three meals for a day – a can of mixed fruit, three crackers, one big cookie, a chocolate bar, cocoa and coffee; and for the main meal, meat and beans with a mixed meat and vegetable combination. The C-Rations included one package of cigarettes, either Lucky Strike, Camels or "a kind of Marlboro," which was Phillip Morris.

They would trade or sell cigarettes and cans of pineapple. A pack of cigarettes sold for $5.

"We had script issued by the U.S. government," he said. The native people would accept the script in payment, and they in turn would receive cash from the U.S. government.

Williamson said there were two Navy-run hospital ships in the Pacific, the "Mercy" and the "Repose."

"They had absolutely beautiful nurses." After he was treated for a wound, he said, "I couldn't get that blonde-haired angel out of my mind. It had been a year since I had seen an American woman."

Korea remembers - Williamson received a proclamation of thanks from the Republic of Korea (South Korea) in January of this year. It reads: "Ambassador for Peace Official Proclamation, Geroge M. Williamson. It is a great honor and pleasure to express the everlasting gratitude of the Republic of Korea and our people for the service you and your countrymen have performed in restoring and preserving our freedom and democracy. We cherish in our hearts the memory of your boundless sacrifices in helping us reestablish our Free Nation. In grateful recognition of your dedicated contributions, it is our privilege to proclaim you an "AMBASSADOR FOR PEACE" with every good wish of people of the Republic of Korea. Let each of us reaffirm our mutual respect and friendship that they may endure for generations to come. January 28, 2016. [signed] Minister, Patriots and Veterans Affairs, Republic of Korea; Chairman, Korean Veterans Association, Republic of Korea." Williamson was a veteran of two major wars by the age of 23.

He said the USO shows "were really important to us. Bob Hope, we really did not want to miss him. He was there all the time."

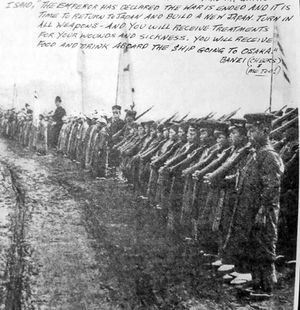

The Americans landed on Okinawa on April 1, 1945. The Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on Aug. 6; the second bomb devastated Nagasaki on Aug. 9, and Japan accepted surrender terms on Aug. 14. Williamson was sent to China to bring Japanese troops and children back to the homeland (see photos). They collected all civilian firearms in Japan, bending the rifle barrels before burning them in a bonfire. Civilians would abandon resistance for a can of food or a cigarette.

Before the U.S. dropped the bomb, Williamson was next on the list for an amphibious landing on Japan.

"We didn't want that. We wanted to go home. I would have given my last dollar to see that nurse again."

"We found out at five o'clock in the morning. They lined us all up and said there was good news– 'Today you will not make the landing at Yokosuka or anywhere on the Japanese coast as we have planned.' There was a cheer."

"I really felt relieved. To lose all my guys again in a combat situation was not what I wanted. Most had been wounded three or four times and had come back."

Williamson returned to cvilian life to be a ski instructor at Sun Valley, Idaho. "It was one of the best parts of my life," he said. Then one day when he was deer hunting, the local sheriff came by to tell him they both had been recalled to fight in Korea. "They're losing their country," the sheriff said.

George Williamson lives in Bear Valley Springs. He likes to golf and is married to Nancy, who is active in AAUW and other civic organizations. Read the rest of Williamson's story in the next Loop.