Rabbitbrush: the golden flowering light of autumn

Land of Four Seasons

October 29, 2022

Jon Hammond

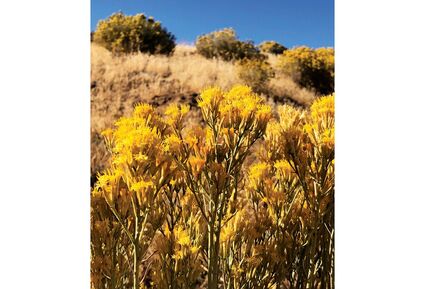

Robust Rabbitbrush shrubs bloom golden on Cherry Lane with Togowakahni (Black Mountain) visible in the background.

One of my favorite aspects of living in the Tehachapi Mountains is how vibrant and tangible the changing of the seasons can feel. The weather, the angle of sunlight, the temperatures, the plants and animals. . . they all shift and pulse seasonally. The longer you live here, the more expected and predictable these patterns are.

Right now, we're in the golden days of autumn, and this is partly due to one of the most significant flowering events of the year in the Tehachapi Mountains: the annual blooming of Rabbitbrush.

As summer fades and autumn brightens, Rubber Rabbitbrush (Ericameria nauseosus) turns from nondescript, pale green shrubs that are easily overlooked into brilliant clumps of golden yellow, alight with glow of late afternoon sunlight.

As more and more Rabbitbrush bursts into bloom, their normally drab foliage is suddenly festooned with small flowers the color of melted butter. But how could Rabbitbrush flower now? It hasn't rained in five or six months. The summers are long and dry. . . Yet bloom they do, in profusion, thanks to their long taproot and ability to withstand rainless conditions.

Bees, butterflies and other pollinators bless the unlikely appearance of Rabbitbrush flowers in all their fall abundance. The flowering of Rabbitbrush suddenly makes a wealth of pollen and nectar available, and incredibly it happens after months of drought.

Rabbitbrush is a drought-tolerant shrub that typically grows between two and five feet tall. It is not an imposing plant, with slender brittle branches and very narrow leaves that look more like the needles on a white fir tree than typical leaves.

Rabbitbrush's sparse foliage is pale yellowish green and for most of the year these unobtrusive plants are hardly noticed, even though they are very common in Tehachapi, establishing themselves along roadsides, on arid slopes, even in cleared fields once they lie fallow.

Rabbitbrush leaves are very small and slender, and the plant will shed most of them in times of drought. But the stems themselves are green and are photosynthetic, so they can perform the food-making services that leaves provide in most plants.

Rabbitbrush around Tehachapi, growing almost anywhere as long as it is undisturbed, is literally abuzz right now with honeybees and other insects making use of the nectar.

This is a time when beekeepers are making sure that their bees have access to Rabbitbrush. My beekeeping friend Christopher Carlberg has been working hard the past week or two moving hives around to locations that are well-placed near flowering Rabbitbrush. In our area, the main wild nectar source in the summer is California Buckwheat, and in autumn it is Rabbitbrush.

Typically beekeepers will leave all the Rabbitbrush honey in the hives to help sustain the bees in winter, while removing tastier honeys like buckwheat, orange, clover, and mixed wildflower and others.

Rabbitbrush honey isn't bad, it just doesn't taste as good as some of the others. Rabbitbrush itself has a distinctive, pungent odor that tends to flavor the honey. It is not an unpleasant smell, but it is strong and recognizable.

I used to stand next to the late Pete Sanders, who was the most experienced of all Tehachapi beekeepers, at his beeyard near the corner of Cherry Lane and Sage Lane. We'd watch as bees returned to their hives from the open fields to the west, bringing in Rabbitbrush honey from the many shrubs in bloom.

"Ya see those taildraggers comin' in loaded with honey, boy?" Pete would ask with his melodious Arkansas-twinged voice, his gold-flecked blue eyes shining as he stood there in faded denim overalls observing his bees, his large strong hands resting on each other atop the handle of the worn shovel he always kept in his bountiful garden.

Pete called them "taildraggers" when they came in weighed down with honey and pollen, their bodies tilted noticeably down towards the tip of their abdomen instead of flying horizontally level.

"Ya smell that honey? It's rabbitbrush, you can smell it just standing here," Pete would point out. "Man oh man, them bees are working hard. They want to fill up their hive before winter comes. I'll leave 'em all the rabbitbrush honey they bring in."

The bounty of abundant rabbitbrush nectar has helped many a bee hive, both wild and domestic, survive a Tehachapi winter, as well as untold numbers of butterflies and other nectar feeders.

Jon Hammond

Rabbitbrush stems are green and can photosynthesize for the plant even when there are few leaves present.

The Nuwä word for Rabbitbrush is tüva-posonü, pronounced tuh-vuh-po-SO-nuh, which means "pine nut needle." The traditional people didn't use Rabbitbrush too much, but they would strip the bark and leaves off a twig, sharpen the end and thread pine nuts on the twig as a way of keeping them. It was said to improve the flavor. Rabbitbrush was also used as thatching outside a kahni (house) if other plant material like tules were unavailable.

It is autumn in the Tehachapi Mountains, the nights have gotten cooler, the days are shorter, and Rabbitbrush is in full bloom. Savoring the changing season. . .

Keep enjoying the beauty of life in the Tehachapi Mountains.

Jon Hammond is a fourth generation Kern County resident who has photographed and written about the Tehachapi Mountains for 38 years. He lives on a farm his family started in 1921, and is a speaker of Nuwä, the Tehachapi Indian language. He can be reached at tehachapimtnlover@gmail.com.