Tules: an aquatic plant anchoring Native culture and wetlands

Land of Four Seasons

October 1, 2022

Jon Hammond

Tules fringe the little lake in Golden Hills named Tom Sawyer Lake during the Golden Hills Golf Course days. It is in the same approximate site as a natural lake known as Teh-HEH-chi-ta that once provided local Indian people with tules for the houses and other crafts.

In any lake, reservoir or pond where water stands year-round in the Tehachapi Mountains, or this part of California in general, sooner or later there will appear a plant that is important to waterfowl and other aquatic species and was of great significance to Native people: the tule, also known as Hardstem Bulrush (Schoenoplectus acutus).

Tules are a type of giant sedge that is found in marshlands all over the West. The long round stems are dark green and grow from three to ten feet tall, with a small cluster of brown flowers and seeds found at the tip of the stalk.

Forming dense colonies, tules provide shelter to an array of wildlife, including many kinds of ducks, coots, herons, rails and other birds. Red-winged blackbirds commonly build their nests in tule stalks, and amphibians also hide among them. Dragonflies frequently use tules as perches and even fish swim in among the submerged stalks.

Tules are nearly always found in standing water or the adjacent shoreline. Tulare Lake, once the largest freshwater lake in the West, had tens of thousands of acres of tule marshland before it was drained by land speculators, and tule marshes served as places where Indians concealed themselves from settlers and later outlaws hid from lawmen.

The Nuwä (Kawaiisu or Southern Paiute) people of the Tehachapi Mountains know tules by the name seevibü, pronounced say-VIB-uh, and Nuwä people traditionally used tules for making sleeping mats, sitting mats, and for both the external and internal walls of their homes. The Nuwä word for house is kahni, which is pronounced kahn-hi.

The outside of the kahni would have woven mats of tules overlapping each other, one on top of the other going upward to the roof like shingles. The tender lower portions of tule shoots were also eaten raw, or chewed like sugar cane. The tule mats were either woven using smaller tules, as shown in the photos that accompany this article, or sewn together with milkweed cordage.

Tules would be gathered from wherever they grew. In earlier times, the lake near Monolith, at the eastern edge of the Tehachapi Valley, known as Proctor Lake now and Narboe Lake to pioneers, had water in it year-round and was fringed in places by extensive stands of tules. This lake was called Owa-vi-va'adä by the Nuwä, which means "Place Where There is Salt," because there used to be large deposits of salt since the lake had no natural outlet and for thousands of years the trapped water would evaporate, leaving salt deposits behind.

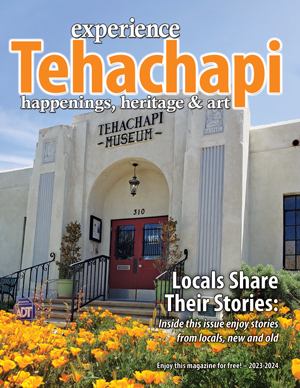

A natural lake in Golden Hills was known as Tehechita, pronounced Teh-HEH-chi-tah, and was located near the present-day site of Tom Sawyer Lake. This small lake provided tules for the villages that were found in the vicinity of Old Town Road. Because water sources were among the first resources seized by settlers, tribal members in later years had to make do with other materials for kahni building.

Tules have been used for a wealth of craft items by different California tribes, including basketry, duck decoys, canoes, cordage and more. Tules grow and spread from rhizomes and are very useful in preventing streambank erosion – they even mute the effect of powerboats, dampening the wake and ripples from passing motorboats, allowing water to pass between their stems but absorbing most of the wave energy.

Tules are a familiar sight at ponds and wetlands throughout our area and beyond, and they are as important to aquatic wildlife as they once were to the Native peoples of California.

Keep enjoying the beauty of life in the Tehachapi Mountains.

Jon Hammond is a fourth generation Kern County resident who has photographed and written about the Tehachapi Mountains for 38 years. He lives on a farm his family started in 1921, and is a speaker of Nuwä, the Tehachapi Indian language. He can be reached at tehachapimtnlover@gmail.com.