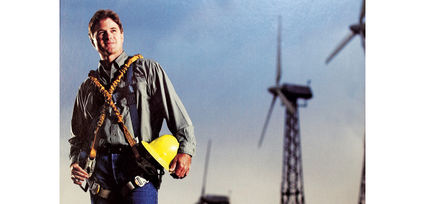

David Schulgen: the unexpected journey of a Tehachapi boy from the Marines to wind industry pioneer

Land of Four Seasons

May 9, 2020

David Schulgen, who made a career in the wind industry starting from its early days in the 1980s, had unambivalent feelings about wind energy when it arrived in the Tehachapi Mountains: "I hated wind turbines. We raised cattle in Oak Creek Canyon, and I liked to explore the hills around Tehachapi, and I didn't like the wind turbines coming in."

His feelings toward the wind industry evolved. But it took some time. The wind industry still didn't exist in the area when Dave graduated from Tehachapi High in 1978. He and one of his close friends, Rod Harrington, had both signed up for the Marine Corps in a deferred entry program while they were seniors at THS, so they went right to Camp Pendleton shortly after graduating, and Dave turned 18 in boot camp. He did the testing to determine his Military Occupational Specialty (MOS), and the results suggested Dave would be well-qualified to be an equipment operator. So off he went to learn about being an equipment operator - except somehow his orders were confused with someone else's and much to his dismay and annoyance, he ended up at basic electricians' school.

"I was terrible at math in school," Dave explains. "I took one semester of math during high school and got a "D" in it. And here I was in a training program for electricians, and there was all kinds of math involved. I was really unhappy about being there."

Dave was soon taken aside by a staff sergeant, he remembers: "That sergeant told me 'You're directing your energy in the wrong place. You can have a bad attitude about being here, or you can focus on learning, and leave here a better man than when you got here.' That helped turn my mindset around and I found that if I applied myself I was pretty good with electricity and basic electrician's skills."

Dave and Rod spent a year of active duty, and then were placed in the Marine Corp Reserves for five years - this was long before the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, so the Marines actually had a few more good men than they needed on active duty. They returned to their hometown to look for jobs.

"At that time, there were basically three places to work in the Tehachapi area: Monolith, Cal Portland and CCI," Dave recalls. "Most kids in school at that time used to say that you would have to leave the area if you wanted to make something of yourself, but I never had any plans to leave."

His first job out of the Marine Corp was working as a water tender at the golf course in Stallion Springs, and then shortly thereafter he got a job at the Cal Portland Cement Company between Tehachapi and Mojave.

Trying the cement industry

Dave's father, Bill Schulgen, was a longtime member of the management team at Cal Portland, and it wasn't a surprise that Dave would apply there.

"I was ecstatic when I got hired," he remembers. "I started at $8 an hour, I was in the union so I got raises on a regular basis, and I was glad to have a job. I was young, cocky and full of energy. I worked as a laborer and later in the packhouse, and then I completed an International Correspondence School course through the company working to be an 'Electrician Second Class' at Cal Portland which mostly ends up changing light bulbs - there's a million light bulbs in a cement plant, and they were constantly having to be replaced."

When there were some layoffs in the early 1980s due to one of the cyclical slowdowns in the cement industry, Dave volunteered to be one of those temporarily laid off. He got by on construction jobs. "I helped Henry Schaeffer build his house in Bear Valley Springs, and I even turned down a few jobs in the new wind construction because I knew that I would get called back," Dave said. "I got called back after nine months." Dave found he had really enjoyed working outside, away from the plant, during his time off. He would also hear friends at BBQs and gatherings talk about working on the new wind turbines that had appeared in the area, and discuss the electrical components, and despite his initial disdain, the conversations interested Dave.

"I started enjoying work at Cal Portland less and less," he remembers, "I had married my girlfriend, Nancy Messier, in 1982, and she knew I was unhappy at work. She has always been completely supportive of me and believed in me, and when I told her that I wanted to try something different, she went along with it." Dave's childhood friend Jon Lantz told him that he could get him a job at Zond Systems, but he would be making $8 an hour instead of the $14 he was making at Cal Portland.

"We were concerned about the big cut in pay," Dave recalls, "We had a house payment to make and had started a family, but I decided to give my two-week notice. I went in to work, it was in early April, 1985, and I was working on equipment, leaning out looking downward and at the same moment I panicked and was thinking I could not quit and make it on $8 an hour a big batch of very fine cement dust dropped on me from above, getting all over my shoulders and back, inside my clothes. . . that was the last straw. I quit that day, without giving notice. My Dad wasn't happy about it and rightly so -- he made his career at Cal Portland, and the plant has been good to our family. 'Don't come crawling back to me when this falls apart,' he told me at the time. I started at Zond the next Monday, on Tax Day - April 15."

Dave liked the work at Zond, climbing the lattice-type towers and being outside in the hills. He suffered an early setback, however: after just three months on the job, a time when he was working at the Wind Wall on a hillside that forms a barrier on the east end of the Tehachapi Valley, Dave ruptured a disc in his back. After a month of pain, he saw a specialist and had the recommended back surgery. So he had worked for three months, and then was off with an injury for three months (and it would have been medically advisable to convalesce longer). It was not an auspicious beginning. But he went back to work at Zond, and he kept learning more as he watched the industry develop and improve. "When I started the machines produced just 65 kilowatts each, then they went to 90kw, then 150kw, 225 kw, 500kw, 750 kw, and now just one wind turbine can produce 3 megawatts," Dave says. "It was like Moore's Law about the processing power of computers doubling every 18 months -- turbines just kept getting bigger and producing more and more electricity. Zond put the first kilowatt of wind energy into the grid on Christmas Eve, 1981, generated from Tehachapi wind, and now the U.S. wind industry produces more than 300 billion kilowatts a year!"

"That never happens in Denmark."

The early years of developing an industry that had never existed before, in conditions as demanding as those in the Tehachapi Mountains, kept things interesting for Dave: "The Danes would come to Tehachapi after Danish machines began to be used here, and there would be some problem or equipment failure due to our powerful winds, and they'd say 'That never happens at home.' It wasn't an industry for the meek or mild. The wind is your fuel, and I've seen winds blow 100 miles per hour here. There's eddies, uplifts, downdrafts. . . wind current is like water, and it's a force to be reckoned with. We learned so much in the early days, things that are simply common knowledge today - like parking into the wind, for example. Guys used to drive up to the job sites on ridges, with intense, powerful winds, and park facing away from the wind. They'd open their door and it would get ripped out of their hand and be bent backwards. At Zond we literally had dozens of truck doors dented from being bent back the wrong way. Now everyone is trained to park facing into the wind - it might make your door hard to open, but if it gets away from you the door is just going to slam closed, not be bent backwards."

Safety procedures and training protocol was always an area that interested Dave, and he was involved in making improvement to industry practices. "We went basically from little emphasis on safety to being extremely safety conscious," he notes. "We used to go up to the Sky River site, on the ridges overlooking the Mojave Desert northeast of Sand Canyon, when it had been freezing and ice had formed on the turbines. We had 200-pound chunks of ice dropping off turbines and smashing truck roofs and hoods, and crushing a controller. Now we don't even allow anyone on turbine sites in hazardous conditions like that. The goal became having zero injury to anyone."

As the years went by, Dave kept rising within the company: "They used to say at Zond that 'You'll never be a manager if you haven't graduated from college,' and then some other guys and I who hadn't been to college became managers, and they said 'You'll never be a director without a college degree,' and yet that happened too. Sky River was my site from start to finish, and I was there for six years and figured I'd retired from there, but I moved up within the company and worked in both manufacturing and O & M (Operations and Maintenance) and I was traveling all over the country and the world ."

A heart attack at age 37

In June of 1998, Dave and his family, which now included Nancy and their four children, were shocked when Dave suffered a heart attack at age 37 while working in South Dakota. He spent nine days in an intensive care unit in Sioux Falls. He was otherwise fit and healthy, and still is, but experienced a nearly-fatal blockage of an artery. He was only off work for a month, but the ordeal did help keep him focused on the importance things in life. Dave stayed with the company when Zond was acquired by Enron Corporation, and then Enron went bankrupt in 2002 and the wind division was picked up by General Electric. "G.E. sent a transition team and one of their guys asked me about my background," Dave said. "I told him that I had 18 years of practical experience, and before I could finish answering him, he said 'Forget everything you've learned.' I thought that was a ridiculous approach so I was the first one to leave the company. I didn't know what I was going to do, but I knew I wasn't going to 'Forget everything I'd learned."

Dave started Airstreams LLC the day after he left GE in 2002 and ended up as a consultant to the industry for a few years, and then in 2006 he and his friend Jeff Duff got a contract with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power to help develop their own wind company to take care of LADWP turbines which eventually turned into Airstreams Renewables, which created an intensive and federally accredited vocational program that trains technicians to be employment-ready for jobs within the energy sector and trains mostly veterans utilizing the GI Bill. Airstreams continues to grow, has schools in other states, and has graduated more than 5,000 students, who now work in the energy or telecommunications industry.

Dave remembers when a woman saw him at a store wearing a wind industry shirt, and she took him to task for "You people coming here and messing up our area with wind turbines, you need to go back to where you came from." Dave asked her how long she lived here and she said "10 years." "I told her 'Ma'am, I was born at Tehachapi Hospital, I grew up here, and was able to stay here and provide my family with a good living because of the wind industry,'" Dave says, "Wind energy production provides hundreds of good jobs for local people, and while I don't think wind turbines should be everywhere and I've been opposed to some wind projects, I feel totally blessed to be doing what I'm doing right here in my hometown."

Jon Hammond is a fourth generation Kern County resident who has photographed and written about the Tehachapi Mountains for 38 years. He lives on a farm his family started in 1921, and is a speaker of Nuwä, the Tehachapi Indian language. He can be reached at tehachapimtnlover@gmail.com.